Young people are socializing less and less — this may be harming their mental health

Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, picks her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

What do the epidemic of loneliness mean, the decline in the rate of drinking among adolescents and acquaintanceand deteriorating mental health among teenagers and young adults have in common?

To begin with, two of them are somewhat controversial. The lack of hard historical data on loneliness has led some to question whether there has even been an increase, let alone an epidemic. And about the mental health of young adults, some claim that a significant part of the observed increase in the problem is simply taking on cases that would have gone undiagnosed before, while others point to wrong statistics.

Skeptics are not wrong to raise doubts, and it is almost certain that there has been some degree of overestimation. But as time passes and data and testimony mount, there is increasing recognition that the absence of specific causal evidence does not constitute evidence of absence. Indeed, there is a growing sense that these phenomena are not only real, but that they are all part of the same broader change: a sharp decline in personal association among young people.

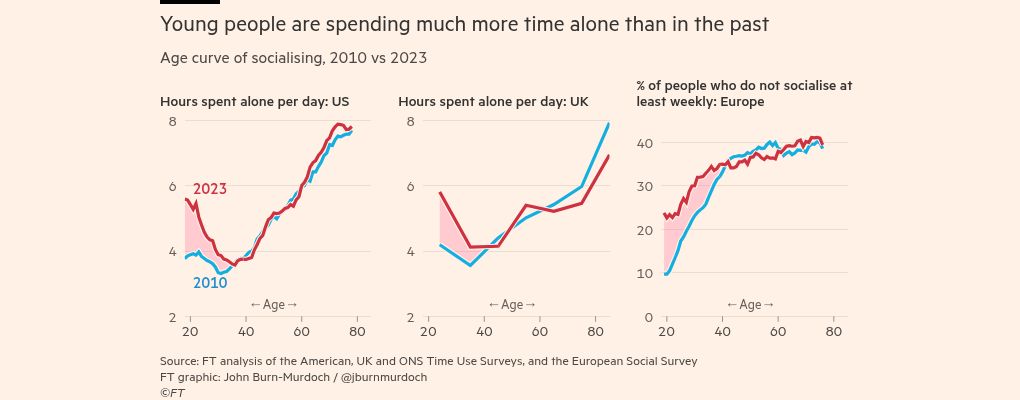

Until recently, there was evidence of loneliness weak at bestbut research that previously showed it was declining among high school students in the US now they show steep climbs. In the UK and Europe, new figures published in 2024 show a significant increase in loneliness among people in their twenties. This reflects patterns in socializing, or the lack thereof. As the Atlantic’s Derek Thompson wrote last week, we increasingly live in antisocial century. Far from being a US-specific trend, this has swept the Western world. The proportion of young people on both sides of the Atlantic who regularly socialize with friends, family or colleagues has fallen sharply. In Europe, the proportion of those who do not socialize even once a week has increased from one in ten to one in four.

People in their teens and twenties now socialize about as much as people 10 years their senior did in the past. It’s not so much the case that 30 is the new 20, as that 20 is the new 30. Less socializing and less partying means less sex and less drinking. Both are news that have been welcomed by the public health community, but they mask a darker side.

Trends in time spent in solitude are almost an exact parallel to trends in mental health, where rates of mental pain they are growing among the young, but not among the middle-aged or elderly. Wealth of public health research suggests that the two are not just coincidental, but causally related. Time spent alone is strongly associated with lower life satisfaction and even increased mortality.

Some of the most valuable evidence comes in the form of detailed time-use records from the US and the UK, which show significant increases in time spent alone among teenagers and young adults over the past decade, but little or no change among older groups. Most importantly, this diary data also captures how people feel throughout the day while doing different things with (or without) different people.

A clear and consistent finding is that more time spent alone is associated with lower life satisfaction, and people report lower levels of happiness when doing the same activity alone compared to company. Using the levels of happiness and meaningfulness Americans attribute to various activities in these records, I find that the decline in young people’s life satisfaction between 2010 and 2023 can be largely explained by changes in how they spend their time.

The most obvious culprit in terms of time and age gradients is the proliferation of smart phones and hyperactive social media, which have gone overboard with the age of short form video. Of all the dozens of activities rated in the US time-use data, hours of solitude spent playing games, browsing social media and watching videos were rated as the least meaningful.

The fact that these ratings are given by the very teenagers and young adults who spend hours glued to their devices underscores the tragedy at the heart of this story: people who are suffering at some level are aware of what’s going wrong, but seem powerless to stop it.

The last decade has been the story of young people retreating from their most fulfilling aspirations and replacing them – knowingly or not – with pale imitations. Like the proverbial frog in a pot of water, the damage is too subtle to cut through at any given time, but in a few years we may be starting to boil.