US stocks most expensive relative to bonds since the dotcom era

U.S. stocks jumped to their most expensive level against government bonds in a generation, amid growing jitters among some investors over high valuations of megacap technology companies and other Wall Street stocks.

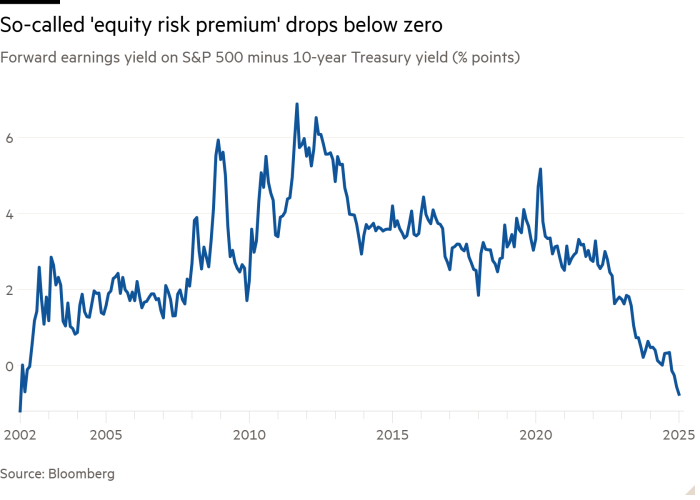

Breaking records for US stocks, which reach a new peak on Wednesday, pushed the so-called forward earnings yield — expected earnings as a percentage of stock prices — on the S&P 500 to 3.9 percent, according to Bloomberg data. The selloff in government bonds lifted yields on 10-year bonds to 4.65 percent.

That means the difference between the two, a measure of the so-called equity risk premium, or extra compensation to an investor for the risk of owning a stock, has fallen into negative territory, reaching levels last seen in 2002 during the dotcom boom and bust.

“Investors are basically saying ‘I want to own these dominant technology companies and I’m willing to do it without a huge risk premium,'” said Ben Inker, co-head of asset allocation at asset manager GMO. “I think that’s a crazy attitude.”

Analysts said that the high values of US stocks, labeled as “the mother of all bubbles“, were the result of fund managers demanding exposure to the country’s high economic and corporate profit growth, as well as a belief among many investors that they could not risk leaving the so-called Magnificent Seven tech stocks out of their portfolios.

“The questions we get from clients are, on the one hand, concerns about market concentration and how difficult the market has become,” Inker said. “But on the other hand, people are asking, ‘Shouldn’t we just own these dominant companies because they’re going to take over the world?’

The traditionally constructed equity risk premium is sometimes known as the “Fed model”, as Alan Greenspan seemed to refer to it when he was chairman of the Federal Reserve.

However, the model has its opponents. A 2003 paper by Cliff Asness, founder of fund company AQR, criticizes the use of Treasury yields as an “irrelevant” nominal benchmark and says the equity risk premium has failed as a tool for predicting stock returns.

Some analysts now use an equity risk premium that compares the earnings yield of stocks to inflation-adjusted U.S. bond yields. On this reading, the equity risk premium is also “at its lowest level since the dotcom era,” said Miroslav Aradski, senior analyst at BCA Research, though not negative.

The premium might even understate how expensive the stock is, Aradski added, because it implicitly assumes that the earnings yield is a good proxy for the future real total return of shares.

With profit margins above their historical average, if they “returned to their historical norms, earnings growth could end up being very weak,” he said.

Some market watchers are looking for completely different measures. Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, sharply criticized the Fed’s model and said the proper way to calculate the equity risk premium is to use cash flow expectations and cash payout ratios.

According to his calculations, the equity risk premium has declined over the past 12 months and is close to a 20-year low, but “definitely not negative.”

The valuation of stocks relative to bonds is just one measure of exuberance cited by managers. Others include evaluating the price of US stocks against their own history or comparing them to stocks in other regions.

“There are quite a few red flags here that we should be a little bit cautious about,” said Chris Jeffery, head of macros at Legal & General’s asset management division. “The most jarring difference is between how US stocks are priced and non-US stocks.”

Many investors argue that high multiples are justified and can be sustained. “It is undeniable yes [US stocks’ price-to-earnings] the multiple is historically high, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s higher than it should be, given the underlying environment,” said Goldman Sachs senior equity strategist Ben Snider.

According to Goldman’s own model, which suggests what the PE ratio should be for an index of U.S. blue-chip stocks, after taking into account the interest rate environment, the health of the labor market and other factors, the S&P is “in line with our modeled fair value,” he said. Snider.

“The good news is that earnings are rising and, even with unchanged estimates, earnings growth should lead to higher share prices,” he added.

US stocks have now regained all that was lost during the decline since December. That selloff underscored concerns among some investors that there is a level of Treasury yields that a stock market rally can’t live with, because bonds — the traditional haven — would look so attractive.

Pimc’s chief investment officer said this week that the relative values between bonds and stocks are “about as wide as we’ve seen them in a long time,” and the same policies that could boost bond yields threaten to hit stocks.

For others, the decline in U.S. equity risk premiums is just another reflection of investors piling into Big Tech stocks and the risks that concentration in a small number of big names poses to portfolios.

“While momentum on the Mag 7 is strong, this is the year you want to diversify your equity exposure,” said Andrew Pease, chief investment strategist at Russell Investments.