A decline in the birth rate increases the likelihood of a sharp decline in living standards

Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, picks her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

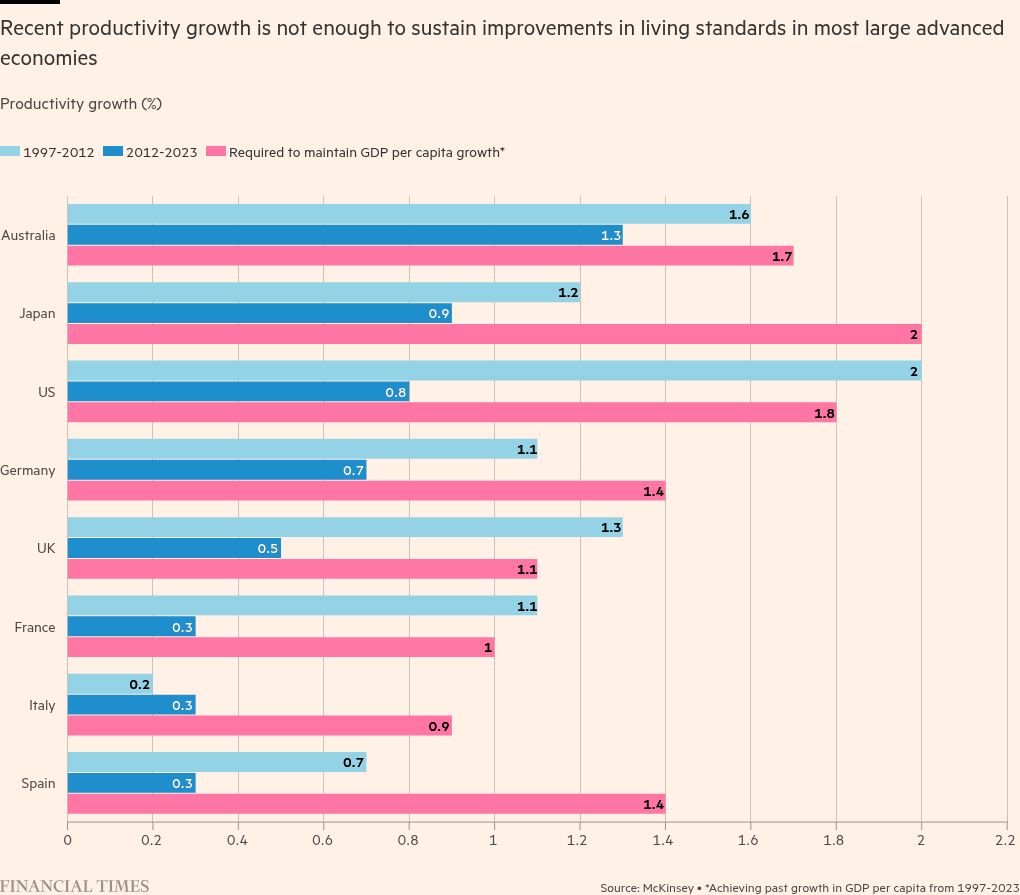

Many of the world’s richest economies will need to at least double productivity growth to maintain historic improvements in living standards amid a sharp decline in birth rates.

A McKinsey report examining the economic impact of falling birthrates found that the UK, Germany, Japan and the US would have to see productivity growth double that of the past decade to sustain the same growth in living standards seen since the 1990s.

A report by the consultancy, published on Wednesday, showed that productivity growth in France and Italy would need to triple over the next three decades to match GDP per capita growth between 1997 and 2023. In Spain, it is set to quadruple between now and 2050.

The report highlights the strong impact of falling birth rates on the world’s most prosperous economies, leaving them vulnerable to a shrinking share of the working-age population.

Without action, “younger people will inherit lower economic growth and bear the costs of more retirees, while the traditional intergenerational flow of wealth erodes,” said Chris Bradley, director of the McKinsey Global Institute.

Governments around the world are struggling to contain the demographic crisis amid rising housing and childcare costs, as well as social factors such as the declining number of young people in relationships.

Two-thirds of people now live in countries with birth rates per woman below the so-called “replacement rate” of 2.1, while populations are already shrinking in several OECD member states – including Japan, Italy and Greece – along with China and many central and Eastern European countries.

“Our current economic systems and social contracts have evolved over decades of a growing population, especially a working-age population that drives economic growth and supports and keeps people living longer,” Bradley said. “This calculation is no longer valid.”

Bradley, who co-authored Wednesday’s report, said there was “not one lever to solve” the demographic challenges.

“It will have to be a combination of getting more young people into work, longer working lives and hopefully productivity,” he said.

The report follows similar warnings from the Paris-based OECD, which last year said falling birthrates put the “prosperity of future generations” at risk and urged governments to prepare for a “low-fertility future”.

McKinsey calculated that in Western Europe, the decline in the proportion of people of working age could reduce GDP per capita over the next quarter century by an average of $10,000 per person.

While some economists believe that generative artificial intelligence and robotics could increase productivity, there is still no sign that this is happening in a significant way. Productivity across Europe has largely stagnated since the pandemic, deepening the gap that developed with the US after the financial crisis.

The consultancy argued that more countries will need to encourage people to work longer, following the example of Japan, where the labor force participation rate among people aged 65 and over is 26 per cent, compared with 19 per cent in the US and 4 per cent. cent in France.

Despite longer working lives, Japan’s GDP per capita has grown at just over a third of the US level over the past 25 years.

“The demographic headwind is relentless and severe, and when it hits, boosting productivity growth becomes even more important,” the report said.

The consultancy calculated that to maintain the growth in living standards at the same rate, the German worker would have to work 5.2 extra hours per week or the share of the employed population would have to increase by almost 10 percentage points from the current level of almost 80 percent among people aged 15 to 64. year.

The UK and US required lower levels of additional work thanks to a more favorable demographic outlook, but Spain and Italy would also need double-digit increases in the share of people in the labor force.