Germany can spend almost 2 euros without getting up to growth

The German government could take over just under 2 euros of debt in the next decade without risking growing from growth, according to an analysis of the financial Times in the Eurozone economist survey, which supports the fiscal basook of Friedrich Merz.

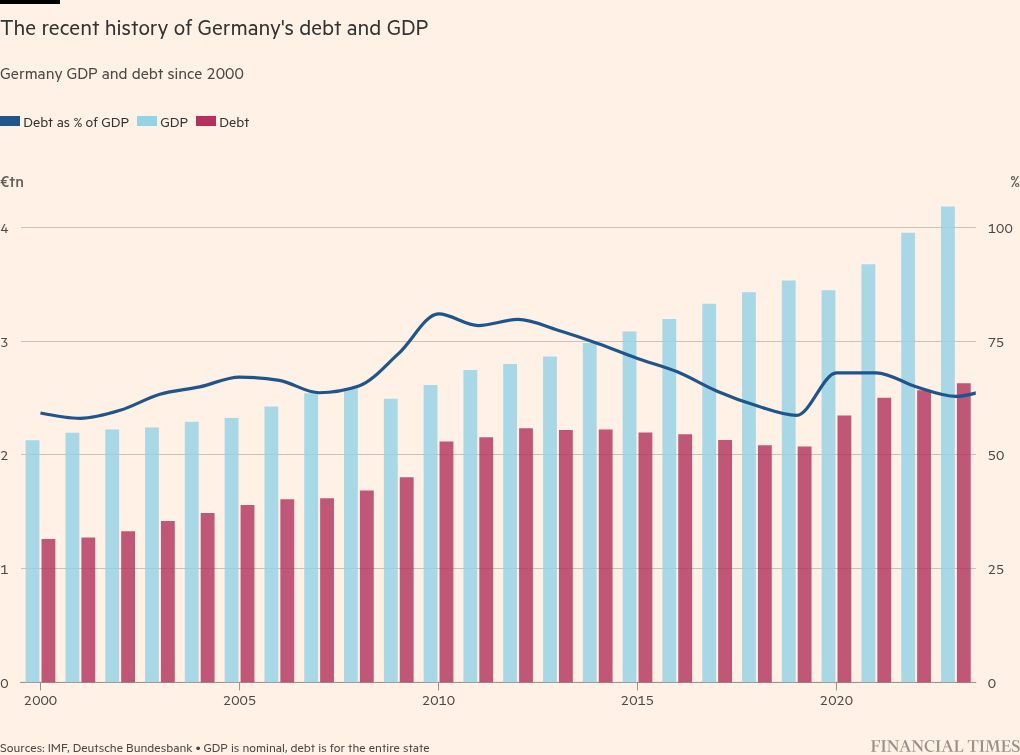

The economist survey conducted last week estimated that the largest European economy could increase the fiscal burden from the current level of 63 percent of GDP to 86 percent of GDP next decade without negative consequences. Answers 28 Economists mean a fiscal space of 1.9tn.

“Germany has great fiscal capacity,” said Marcello Messori, a professor at the European University Institute in Florence, adding that the space to create more debt should be used to push Germany and the wider European economy according to the “High Technological Sectors and Effective Green Crossing.”

The findings come after Merz, the head of the Christian Democrats of the right centers, and his probable coalition partner, Social Democrats, on Tuesday presented plans to increase the sum of infrastructure in the country and increase the costs for defense.

Economists predict that a fiscal basook, which follows more than five years of economic stagnation, would be needed to lead to an additional 1 euros in public borrowing in the next decade.

“The key point,” said Jesper Rangvid, a professor at the Copenhagen Business School, who estimated that the control of the control debt was 80 percent “or maybe 90 percent” was that Germany was “a space for responsible borrowing” to pay urgently needed improvements and improvements of infrastructure.

“Critical infrastructure, such as not -finishing the inefficient rail system and in general its infrastructure, also digital infrastructure, must be upgraded,” he said.

FT calculation of 1.9tn euros in the fiscal area assume that German nominal GDP will increase by 2 percent annually from 4.3tn to 5.4tn to 2035. This assessment is likely to be conservative because it does not mean that the actual growth of GDP is if inflation coincides with 2 percent of the goal.

Many participants emphasized that additional borrowing should be combined with structural reform to increase the productive ability of the country.

“The money itself will not resolve the challenges,” said Ulrich Kater, the chief economist of Frankfurt’s Deca Bank.

Willem Buiter, a former main economist Citi and an advisor at Maverecon, described the German economy as “grotesquely over-regulated”.

On Saturday, the probable coalition partners presented further details of politics that clash with the calls of economists.

Instead of cutting bureaucratic reforms and release a growth reform, the coalition has probably promised new state benefits-in-law by boosting larger pensions for mothers who have not worked, VAT cut for restaurants and re-introduction of fuel subsidies for farmers.

Bert Flossbach, co -founder of the German manager of Flossbach von Storch, said on the eve of the announcement on Saturday that the flexibility of the new government could consume a large defense “more space to increase social consumption and even more inflating the state of well -being.”

Lorenzo Codogogno, founder and main economist LC Macro Advisors, said the German “real problem” is his model that has prevailed in the last 20 years, dominated by “sophisticated but old industry.” Germany also needed “leading, innovative companies,” he said.

“The German industries are stuck in the middle technological trap,” and the country was to “modernize” its production, said Antti Alan, an economist at the Finnish Center for a new economic analysis.

Stefan Hofichter, an economist of Allianz Global Investors, blamed the suffocated bureaucracy and tax regime, saying that the economy had pulled “too solid bureaucracy” and “too high profit taxes” that “contributed to private insufficient investments.”

Jörg Krämer, the chief economist Commerzbank, invited Merz to call the influence of the state on the economy and to “trust citizens and corporations”, instead, in the fee for “better business conditions”.

The discoveries were based on 28 quantitative answers to the question of whether, leaving aside by any legal limit limit, Germany increased its federal debt without growth.

A widely quoted 2010 study by Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart suggested that a debt greater than 90 percent of GDP causes damage to growth, but subsequent research challenged this conclusion.

“Economic literature does not provide a definitive response to the appropriate level of public debt,” said Isabelle Mateos Y Lago, the main economist of the group in BNP Paribas, adding that the debt dynamics were guided by nominal growth and costs of borrowing.

All 41 economists who answered the question about the strict German debt brake, which locks additional consumption at 0.35 percent of GDP, said that the borrowing rule, from 2009, should be alleviated.

More than a quarter – or 29 percent of respondents – it said it should be completely abolished, which is 41 percent or removed to ensure “much greater flexibility”. The remaining economists supported moderate reform to enter “a little more flexibility”. No one called the rule to leave him unchanged or harden him.

“[The] The German obsession with fiscal prudence is exaggerated, and the reforms are late, “said Martin Moryson, a global economy chief in the German DWS assets, adding that the arrival Government” obviously “realized” the size of the task and stands out for the challenge. “

However, the Law of Green’s legislators said on Sunday that in their current form they opposed Merz’s plans to create a fiscal space through moving costs for defense above 1 percent of GDP outside the debt brake.

Their opposition could prevent plans, which require changes in the German Constitution and two -thirds of the majority in the Parliament above House, Bundesrat, to pass.

Oliver Roeder’s data visualization in London