Why can governments not pay for the higher birth rate

Politicians in Lestijärva thought they had a response to Finnish demographic troubles: every mother of a newborn baby would receive 1000 euros a year for 10 years if they remain in the second sweetest municipality of Nordic countries.

But more than a decade after they introduced payments and over 400,000 euros in poorer, officials were forced to recognize the defeat: Lestijärga’s population has decreased for a fifth since the scheme started.

“It’s not worth doing at all,” said Niko Aihio, a former head of education in the city. “Baby Boom lasted only a year.”

Politics donors around the world face the same problems as those in Lestijärva: no matter what they seem to offer in a way of incentives, people have no more babies. The Finnish municipality did not even manage to lure people from somewhere: “He did not stop the people who moved away and did not attract new families,” Aihio said.

China has offered free fertility treatments, Hungarian great exemption from tax and cash, and Singaporean scholarships for parents and grandparents. The Danish passenger company even led the advertisement campaign to “do it for Denmark.” In Japan, the state fundes a match to AI, while Tokyo’s metropolitan government offer A four -day working week of staff in an attempt to encourage people to become parents.

Governments are still hunting for political capabilities in order to counteract the outpatient economic crisis as the older population is spreading and a set of workers decreases. It is a shift that the Think-test of the Robert Schuman Foundation called “demographic suicide”

The reasons for the trend were fiercely discussed, while some potential solutions, such as immigration and push people, were to be drawn deeply politically unpleasant.

“The issue of population aging is more challenges for Europe,” said Olli Rehn, a Governor of Finland Central Bank. “First, the ratio of dependence exacerbation exerts significant pressure on public finances. Second, aging society is usually less economically dynamic and less entrepreneurial. “

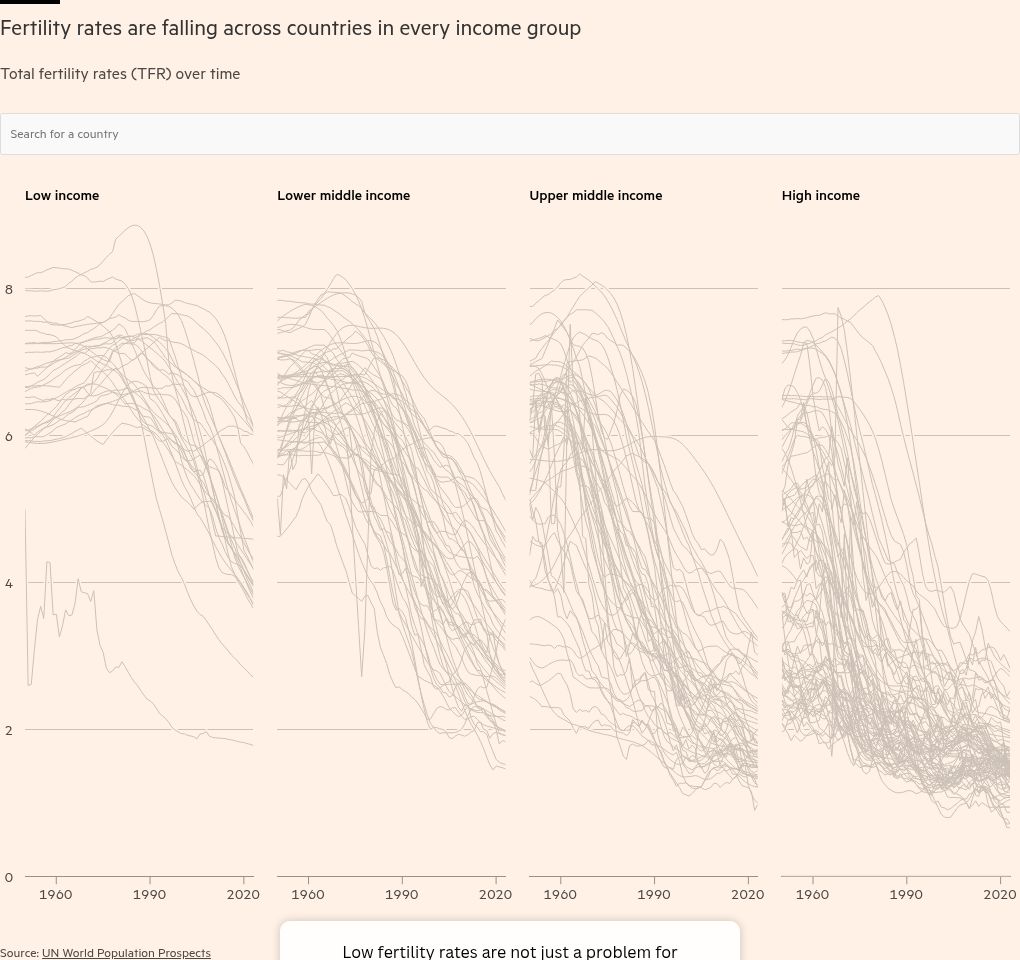

The decline in birth rates is an unusual universal problem – the trend has not remained an intact continent. Two -thirds of the world’s population now live in countries where people have babies too low to replace their population.

More and more countries are joining the list. By 2100, only 12 countries are expected – 11 in Africa and the tiny island of the Pacific Ocean Vanuat – have a fertility rate above a key level of 2.1 birth per woman. One country is not expected to have a rate above 2.3 to the end of the century.

Politics donors can be tempted to focus on more direct crises. But the fall of fertility rate threatens to lead to a deep economic discomfort. Less babies and more older residents lead to a lower share of people of working age, pouring tax revenues at the same time as increasing the costs associated with the aging of society, such as state pensions and health care.

Without enough policy action, S&P Global assessment agencies have estimated in 2023 that a fiscal deficit balloned up to 2060 from a global average of 2.4 percent of GDP to 9.1 percent. Global net government debt to GDP level would almost triple.

Meanwhile, a McKinsey Report In January, they suggested that many richest economies in the world, such as the UK, USA -ai Japan, would need at least twice a double growth of productivity to maintain historical improvements in life standards in the midst of sharp falls in their birth rate.

Parts of Asia, especially China, and Latin American countries are especially exposed. In 1995, 10 workers in East Asia supported one age; By 2085, it is predicted to be one to one.

Baby gap

This is the first article in a row about the upcoming global demographic crisis because the population level should be reduced

1. Part: Politicians want more children but their policies are failing

Part 2: Kenya – a window into the demographic future of Africa

Part 3: A country that migration leaves behind

Part 4: South Korean city where the birth rate has reached ‘extinction’

Politicians care that they could be powerless to act, because social pressures on women undergo a deep change. Sarah Harper, Professor of Gerontology and Director of the Oxford Population Institute, said that exploring young women around the world, from Europe to Southeastern Asia, suggested a once built-in social obligation that women reproduce and the assumption of their part if they could, would probably have had, Children – no longer existed.

Careers and increased gender equality are part of this. “We have a whole group of women in high -income countries, but also in Southeast Asia, and especially East Asia. . . who were educated in a very native neutral way, “Harper said.” They enter a job in a native neutral way, and then become parents and suddenly, no matter how hard he tried, it’s not a native neutral. ”

Politics will also have little effect where the norms around the number of children are installed. Harper noted that in China, despite the end of the policy of one child in 2016, women still had only one child.

“Once you come to a single child’s company, why would you like to have two children? Because everyone has one child .. All are focused on one child. The institutions are aimed at having one child,” Harper said.

Heidi Colleran, an academic from the Max Planck Institute for evolutionary anthropology in Germany, said that despite decades of research and thousands of people working on demographic trends, there are few consensus on why fertility rates are constantly declining.

“There are many general threads that can be withdrawn: an increase in nuclear families, changes in the age of marriage, the speed that people live together, the age where people begin to have their first child become older and older,” he said. “There are many of these features at the level of individuals. [But] The same constellation of predictors, they will be connected to each other in a different way in different places. “

However, although the personal choice has played a role in the global fall of children, the studies show that people often have fewer children than they would like – which indicates that there may still be a role of public policies in changing it.

Obrants such as care costs for children and apartments, financial instability, permanent gender inequality, non -inflexible working conditions and lack of work security are the factors that prevent people from having more children.

Better policies may not be able to completely close the gap, but I can help you. “Supporting family policies – such as affordable care of children, financial incentives and cultural acceptance of work parents – can significantly affect demographic trends,” Rehn said.

Experts agree. “A conventional pronatal policy that blows money in a problem acts to some extent,” said Lyman Stone, a demographer from the Institute for Family Studies, which specializes in fertility.

Stone said studies show that fertility rates in South Korea could even be lower than now without a baby bonus program, the spread of children funded by the state, subsidized fertility treatment and residential assistance.

At the same time, Finland still remains one of the fastest societies of the world thanks to the big Baby BUM after World War II. It seems that neither cheap children’s care, nor “money for babies” paid by dozens of municipalities, did not have much influence on the birth rate in the country, which remains among the lowest in Europe.

Aihio said that good local services – like libraries, pools and decent care concerns – seemed more important than money in encouraging women to babies. And Rehn admitted that politics could last “long” to show any payment.

Some governments also faced criticism for targeting measures to encourage people to become parents. IN Italy, for example – Where the fertility rate stands with a modest 1.2 – only heterosexual, married women are allowed to undergo fertilization, even private. Single women and those in same -sex partnerships have been rejected access.

The second “huge headache for creators politics,” said Paula Sheppard, an evolutionary anthropologist at Oxford University, was that different parts of the population needed different policies.

Low levels of education delay children for concern about the stability of their relationships and the need to live near their parents. In contrast, those who care about giving up a career ladder with university education and want a practical partner suggested her research.

Others who study the challenge of addiction to age claim that there is no need for policy changes to focus primarily on born.

Edward Paice, an expert on a demographics who focused on Africa, said there was an obvious answer to the demographic problems of the West: Immigration. “Europe cannot be Hermetically anyway. There are huge opportunities for Western countries to reconsider how to deal with African countries,” he said.

The influx of foreigners in recent years slowly but constantly increasing the Finnish population. But although Rehn admitted that immigration related to work and education is “an important part of the solution,” he added: “Of course, in the time of populism, this is a politically challenging message.”

Governments also want people to work longer. Harper, a professor of gerontology, said it was important for societies to admit that the withdrawal from the workforce was, and then expected to live on social support decades after that, “it’s just not sustainable.”

Like immigration, raising pension can come at a steep political expense.

In France in 2023, People went out to the streets In protest while President Emmanuel Macron broke through the legislation to obtain a retirement age from 62 to only 64. Many Chinese responded angrily to legislation to raise legal pension age, which are of the lowest in the world.

“You can increase migration rate or retirement age or encourage people to have more children,” said Edward Davies, director of politics at the Center for Social Justice in the UK. “I doubt three people would naturally like to have families, while they actually tell them they have to withdraw later or have to have a mass migration – this is probably just less popular.”

Additional David Pilling reporting in London