Why is wage growth in the UK so strong?

The salary power in the UK is a puzzle for economists – and a growing problem for the Bank of England policy.

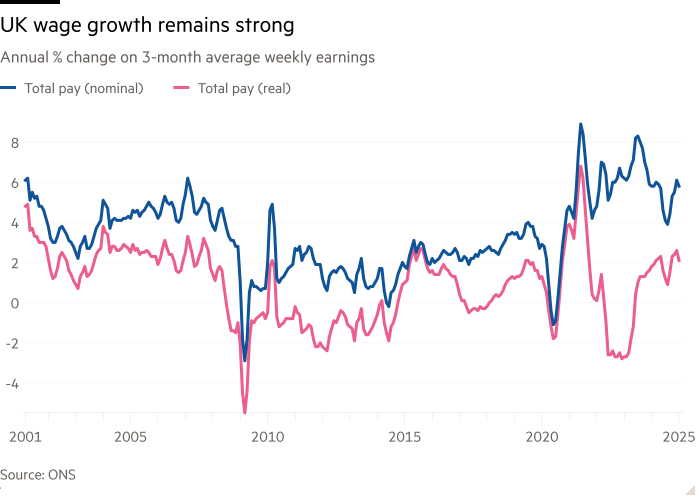

Inflation nagation, widespread lack of work and wave of strikes in the public sector increased the growth of average nominal earnings in the UK to a record high 8.3 percent in the summer of 2023. Since then, the economy has stopped, and the vacancies have failed, and employers put the brakes. Productivity, a long -term determinant of the salary, declines since 2023.

Still, the average earnings in three months by January were still 5.9 percent more than a year earlier – and surpass the inflation over a year and a half.

Bore pay packages are increased for household finances, but also to care for Boe, which sees current growth rates as an inflationary unless supported by better productivity.

Understanding what is happening, therefore it will be crucial for the odds of interest rates.

Is the growth of wages really strong as it looks?

Boe’s Moetary Policy Committee has diminished the latest official salary information because he announced his decision to leave interest rates unchanged at 4.5 percent on Thursday.

An increase in average weekly earnings of 6.1 percent have been encouraged by some sectors where wages growth is often unstable, it is said. The other indicators were in line with the estimation of BOE, published in February, the basic growth of paying just over 5 percent.

But that still means that the growth of salary is “at an elevated level and above what could be explained by economic basics,” MPC said.

MPC added that one of the two major risks to focus on the meeting in May would be “to what extent there could be more persistence in domestic wages and prices.” The second risk he labeled was geopolitical tension pushed the economy into a deeper fall.

Will payments will fall?

Wage growth looks like it would slow down over the next year. Official data show payment pressure in the last few months. Boe’s surveys and data collected by the Brightmine Research Organization suggest that employers will award awards for salaries to existing staff between 3 and 4 percent in 2025.

Some employers will squeeze the payment awards for 1 to 2 percentage points to make up for the impact of higher salary taxes since April, BOE agents revealed.

But Rob Wood, the main British economist at the Pantheon consulting macroeconomics, said it would still leave the growth of earnings above 4 percent on the measure of ONS – too high to be in accordance with the retaining of an inflation to a goal of 2 percent, in the absence of greater productivity.

What drives him?

One of the possible factors is a number of major increases in legal minimum wages. This usually does not affect medium earnings. But employers like the sellers have been alerted by the “shooting effect”, increasing wages for staff that increase the rankings more to ensure that there are still incentives for progress.

Changing the job mix in the economy could also be part of the explanation. The data published on Thursday show that employment in the retail sector with low salaries has fallen last year, while more people are employed in professional fields and in financial services.

But Xiaowei Xu, a senior economist of research at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, Research Tissue, said these factors can only explain the “tiny fraction” of interrupting the connections between growing salaries and states of the economy.

The further possibility that Boe Andrew Bailey’s Governor has floated – this productivity growth may not be as awesome as official data suggests – does not assure economists.

“Like,” wrote Greg Thwaites, Director of Research in Think-Tank Foundation of the Resolution Foundation, recently blog.

Why is the Bank of England worried?

The great concern for Boe is that something has changed in the structure of the British economy, which means that workers and employers are now adapting to “new normal”, where wages grow to 3.5 or 4 percent a year, and inflation hovering a closer 3 percent.

“That would be more expensive to change if it is rooted,” Claire Lombardelli warned, a Boe’s deputy Governor, at the end of 2024.

Wood claims that this is already happening, and creators of “too much Sanguini” policy about a significant increase in household expectations of inflation five and 10 years in advance.

In the years that led to a coined pandemic, the annual increase in salary of 3 percent became a standard because people expected the inflation over an average of 2 percent over time, he noted. Now “households expect the Bank of England to do absolutely nothing … and allow inflation to move forever above the goal.”

Why don’t households spend?

An additional puzzle is why the profit gain in actual teranks does not yet increase consumer consumer consumption. Official statistics show that both retail sales and total household consumption remain below their level before the pandemic, and people have saved the historically high share in their revenue.

Analysts say consumption should be picked up after households renewed the buffers that were spent during pandemic. However, people continue to worry about increasing the cost of food, energy and apartments, threats to reducing jobs and public spending, and talks about trade wars and rent.

Sandra Horsfield, an economist at the Investec Investment Bank, said that the need for more defense consumption will be “disturbing” for consumers in the UK, as well as threatening US tariffs leaving people “wondering how [UK] The general economic situation will apply. ”