Faced with the early beginning of Alzheimer’s, she fought for the extension of a assisted suicide in Quebec

One recent evening, Sandra Dismontigny tried to write down when she would die.

“I sat in a candle corner beside me, just to create my own bubble, think and cry a little,” she said.

For years, she was thinking about this moment, she was desperately hoping for it, fought tirelessly for that. But the words refused to go out. The pattern remained empty before it. How exactly, does it decide when to end someone’s life?

The Canadian province of Quebec, who speaks French last fall, has become one of the few places in the world that allows a person with a serious and incurable illness to choose a medically assisted death in in advance – Maybe years before the act, when a person still has a mental ability to make such an important decision.

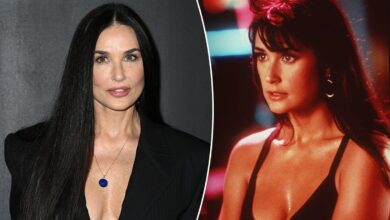

And Mrs. Dismontigny-45-year-old mother of three children, diagnosed with the premiere of her life with a rare form of Alzheimer’s early beginning, has built a major role in lobbying to change.

Some face such a difficult health challenge may be withdrawn. But even when Mrs. Disaux-Noe-Tee-Gnee began to lose his memory, she became the face of a campaign to expand the right to death in Quebec.

In front of the Minister of Health and the Legislators, on the Talk shows, in countless interviews, she spoke about how she inherited the Alzheimer’s gene who was carrying her family. She recalled that her middle father, in the last years of his life, became unrecognizable and aggressive. She wanted to die with dignity.

However, four months after Quebec has expanded the right to death, she had yet to fulfill the advanced patterns of the request. Choosing death was painful enough, but Mrs. Dismontigny had to declare, in precise details, the circumstances under which a deadly dose would be applied. Should she spend it when she needs care during an hour? When no longer recognizes his own children?

“Although this is a topic that has been occupying me for years, now it is different because I have to apply for an official request,” said Mrs. Dismontigny. “But I’m not changing – that’s for sure.”

According to the new law, an advanced request for a assisted death must be fulfilled by a set of criteria and approve of two doctors or specialized nurses.

Only a few countries around the world – including the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Spain and Colombia – recognize in advance the demands for aided death, though, in some cases, not for people suffering from Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia.

In her one -bedroom apartment, Mrs. Dismontigny spoke during a two -hour interview, which was often accentuated by the cries of a very missed Siamese cat named Lithuania. Her partner André Securs was visited – helping her recall the details, reminding her of a scheduled phone call in the afternoon or meeting the next day.

Although she was only in the mid-40s, Mrs. Dismontigny moved into an apartment of residences for the elderly people to Lévis, the suburb south of Quebeca-because she had to help her a year ago. She decided to live alone, not wanting to burden her family. Her two older children were already grown up, and the youngest went to live with her ex -husband, Mrs. Dismontigny.

Her front door was covered with reminder notes. The timer at the top of the savings range automatically excludes power. Dresses in her wardrobe are methodically arranged and archived by photos on their smartphone. No system, however, was impenetrable.

“I’m doing something,” she said, “and Lithi passes by me, and I follow Lithuan and forget what I was doing.”

The bright covers of the couch – returned from Bolivia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and other places where she worked as a midwife – hinted at her life before the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s at the age of 39.

Mrs. Dismontignny decided to become a midwife after the difficult birth of her first child. The accuser, she said, did the procedure without warning.

“That’s my body – can you at least tell me?” Said Mrs. Dismontigny.

As a midwife, she wanted women to give birth in a respected and natural environment.

There was a direct connection for Mrs. Dismontigny between proper birth and appropriate death.

“Life and death resemble each other,” she said.

When Mrs. Dismontigny found out she had Alzheimer’s, she flew into depression but was not surprised. Several older relatives began to experience the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease at a young age, although the disease were hidden as long as they could, without embarrassment.

Her father started losing his memory in his mid-40s and stopped working at 47 at home, he spent days wandering, leaning on the walls and collapsing from exhaustion. In the last years, he licked the floor in the health care institution and played threatening, even threatening to kill his son, brother of Mrs. Dismontigny.

Like many Québécois families, Mrs. Dismontigny’s parents moved away from the Roman Catholic Church, and Mrs. Dismontigny considered herself an atheist. Yet, when her father died after years of anxiety, she said she felt his soul leaving.

“I didn’t see him so, in peace, at least 10 years,” she said.

While her parents’ generation was silent about Alzheimer’s illness, Mrs. Dismontigny set Facebook page 2019 describe life with illness. Postering social media from the mother of three, who is not yet 40 years old, who had to give up her career as a midwife because of the rare form of Alzheimer’s disease, echoed in Quebec. She became a spokeswoman Federation of Quebec Alzheimer Federation and wrote a book about her experience, “Urgency for life. “

Quebec legalized a assisted death ten years ago, before the rest of Canada. According to the law, the person had to be in “”Advanced state of irreversible drop in ability“AND”must explicitly confirm your consent immediately“Before the support of death. But the demands were a problem for those who suffer from incurable and serious illness such as Alzheimer’s disease, who probably lost their ability to consent.

Dr. Georges L’Espérance, Neurosurgeon and President Quebec Association for the right to die with dignitysaid Mrs. Dismontigny helped the press to allow pre -requests after becoming a spokeswoman for the 2022 Group 2022.

“She played a primordial role,” said Dr. L’Espérance. “It’s okay to discuss these concepts in the summary. But it is different when you can associate the disease with someone with whom people can identify with. And Sandra is an open book and very credible. “

Mr. Securs, a partner of Mrs. Dismontigny, said that the fights for change helped to fill the void created by her diagnosis.

“She never expected to devote herself to a class,” Mr. Secors said. “But it saved her, it made sense to her.”

In half a decade since her diagnosis, Mrs. Dismontigny led her hectic life-speaking, writing a book, becoming a grandmother. She embarked on a romantic relationship with Mr. Secours, 72, who lived across from her old place across the street.

“André talks to everyone, welcomes everything, she’s very cheerful,” said Mrs. Dismontignny.

“We were friends, neighbors, at first, then our affection developed,” Mr. Secors said.

Some, however, asked him why he decided to connect with someone with an incurable disease.

“Even my mother, who has only turned 100 and sees me very well, told me,” André, you really don’t make your life easier. “

“She doesn’t say that anymore,” Mrs. Dismontignny interjected.

Last year, the couple rested in Costa Rica and hoped he would go to Safari in South Africa, they said, while Litcha was now sleeping before television.

Perhaps this, a life in which she was still able to lead and enjoy it, made it difficult for Mrs. Dismontigny in writing, as the law demanded, “clinical manifestations“This will lead to a assisted death.

Since Mrs. Dismontigny is likely to become incapable of consent that her illness is progressing, the manifestations she describes “will” represent the term “her consent in the future.

In fact, she wrote In her book that she wanted to carry out a supported death when certain conditions were fulfilled, including that he was unable to recognize even one of his children and aggressively treat her loved ones. But even though she knew exactly what she would say while sitting over the documents in that last dinner, she could not be brought to the record, not yet.

“I will not change my mind because for me, in my situation, that is the best end to the end,” she said. “But I don’t want to die. I’m not ready. That’s not what I want. “