‘Treat us like humans’: Fishing wars trap Indians in Sri Lankan waters | Climate crisis

When Ashoka* heard the approach of the boots, he began to tremble with fear. The 23-year-old was in the engine room of his ship as three members of the Sri Lanka Navy (SLN) boarded the ship. When Ashoka, an Indian fisherman from Pamban Island in India’s southernmost tip, went on deck, he saw officers beating and pushing the eight fishermen on his boat, using guns, iron rods and wooden logs.

The ordeal lasted for an hour, and one of the uniformed men shouted, “Beat them harder, harder,” recalls Ashoka, who was also beaten.

The fishermen – all Indians – were later handcuffed and chained, the steel edges cutting into their skin and causing itchiness. Bound together, none of them could move; otherwise they would all fall. The fishermen were taken to a naval camp in Karainagar, north of Sri Lanka. Fifteen days later, two men – who the fishermen would later learn were from the Indian embassy in Colombo – visited them and gave them towels and soap. The men were finally released a month after they were arrested.

It was 2019, and the fishermen were arrested Katchatheevu, an uninhabited island which comes under the territory of Sri Lanka, for fishing in the waters of that country. Yet the horrors of Ashoka’s experience have since become more commonplace — peaking in 2024, with a sharp rise in the number of Indian fishermen arrested by Sri Lanka, amid rising tensions over allegations of ill-treatment by military authorities in custody.

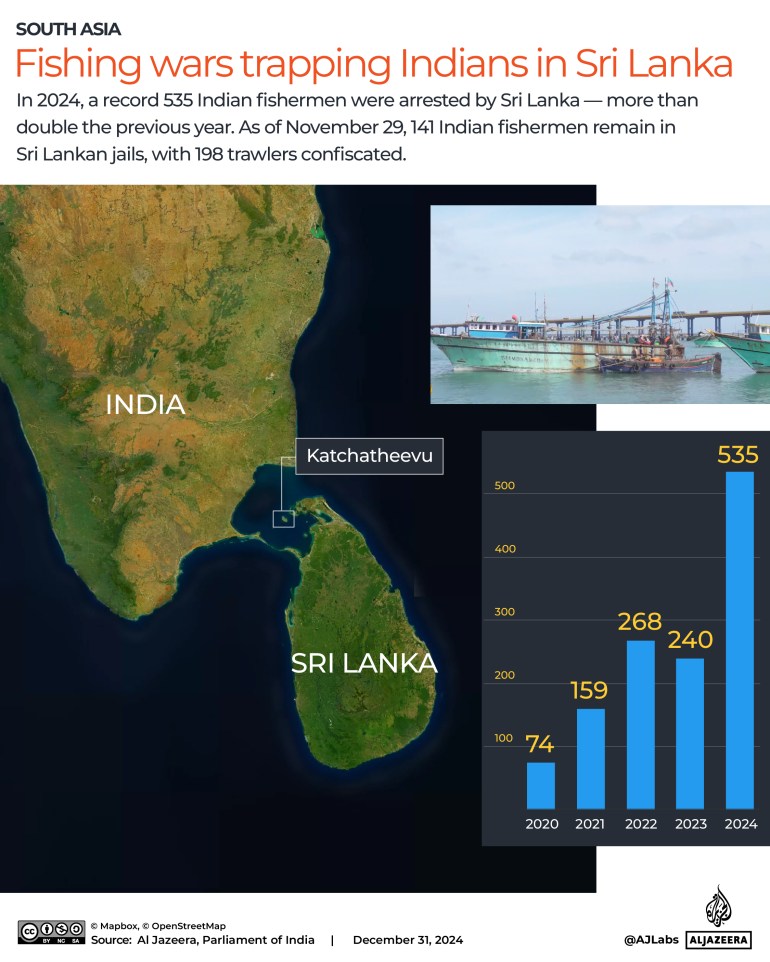

According to Indian government data, Sri Lanka arrested a record 535 Indian fishermen in 2024 – almost double the number of the previous year. As of November 29, 141 Indian fishermen remained in Sri Lankan jails, with 198 trawlers seized.

In September, five fishermen who crossed into Sri Lankan waters returned to Pamban with tonsured heads after being arrested and – according to the fishermen – treated like convicts. They had to pay a fine of 50,000 Sri Lankan rupees ($170) each to secure their release.

Within the fishing community in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, where the Pamban falls, protests have erupted against their government out of frustration that New Delhi has been unable to ensure their safety. Meanwhile, in Sri Lanka, three other Indian fishermen were sentenced to six months in prison and fined.

The SLN and the country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to Al Jazeera’s emails seeking comment on allegations that Sri Lankan officials mistreated the arrested fishermen.

“I would like to be treated like people,” says Ashoka.

‘It’s our hunting ground’

The Gulf of Mannar, an inlet to the Indian Ocean that connects India and Sri Lanka, is rich in biodiversity and a source of livelihood for the fishermen of both countries. Kachchatheevu, a tiny island in the Palk Strait, the part of the ocean that separates the two countries, has historically been a joint fishing ground for Indians and Sri Lankans. Indian fishing rights in the region were terminated in 1976 after India ceded the island to Sri Lanka in 1974. Today, Kachchatheevu is the place of frequent arrests of Indian fishermen.

For Indian fishermen in Pamban, crossing the sea border into Sri Lankan waters is a matter of survival.

Catches on the Indian side have been declining due to climate change, increasing marine plastic pollution and rampant use of mechanized trawlers over the decades. Trawlers, which scrape the seabed in search of fish, destroy seabed habitat, including coral reefs. This in turn interferes with reproductive cycles. Maritime experts also blame trawlers for sea pollution due to abandoned nets and fuel spills.

The seabed on the Indian side is rocky, and the international boundary near fishing towns such as Rameswaram in Pamban begins just 12 nautical miles (about 22 km) offshore, reducing the fishing area for Indian fishermen. For these fishermen, the waters right next to the sea border are legitimate territory to enter.

“It is our hunting ground. Fishermen cross the border knowing full well that they could be arrested or even die. If the fishermen come back without fish, they cannot survive,” says P Jesuraja, president of the mechanized boat fishermen’s association in Tamil Nadu’s Ramanathapuram district.

However, often fishermen enter Sri Lankan waters without the intention of going there, he added.

“Almost half the time fishermen drift to the Sri Lankan side because of water currents or if it’s very dark or raining,” says Jesuraja.

“Fight between fishermen”

In many ways, experts and fishermen alike accept that India has contributed to this crisis through the policies it first pushed seven decades earlier.

Starting in the 1950s, with the support of international funding, India encouraged the use of trawlers. The result was a sharp increase in the income of Indian fishermen, but at the cost of destroying coral reef formations. On the other hand, the Sri Lankan side has a relatively rich fish population: the waters are shallower and the country has a wider continental shelf that is more suitable for fishing. Sri Lanka’s marine ecosystem is richer than India’s also because it does not allow trawling.

The fear of Sri Lankan fishermen that Indian trawlers in their waters will eventually lead to a decline in marine populations – just as happened in Indian waters.

“This looks like a fight between the fishermen of both countries,” adds Jesuraja.

Although the Indian government is holding diplomatic talks with Sri Lanka to secure the fishermen’s release, it is unable to return their boats — a lifetime investment gone forever, Jesuraja said.

Adding to their problems, the United States imposed a ban on Indian wild shrimp in 2019 because the country’s vessels often do not use what are known as turtle exclusion devices. These devices allow turtles accidentally caught during fishing to escape. India has no regulations requiring the use of these devices, so fishermen avoid using them.

India’s Seafood Export Development Authority (MPEDA) estimates that the country has lost $500 million in shrimp export earnings since the US ban came into effect. That ban, in turn, meant that other countries could bargain for lower prices while looking to buy Indian shrimp, Jesuraja says.

The rising price of diesel has also hit Indian fishermen. “Earlier diesel was 50 rupees [about $0.6 at the current rate] liter, and a kilogram of prawns would be sold at 700 rupees [$8]. Now the price of diesel is almost Rs 100 per liter and a kilogram of prawns is sold for Rs 400-500 [$4.6-5.8]”, says Jesuraja.

‘Less fish, more plastic’

However, Jesuraja argues that climate change and increasing marine pollution are the biggest challenges facing Indian fishermen.

“The problem in India is plastic waste, not trawlers,” he says. “Reducing plastic waste will solve half our problems.”

“About 10 years ago, when we put fishing nets in the sea, we only caught fish. Today, the amount of fish is less than plastic waste,” says Marivel, a fisherman from Pamban Island, Tamil Nadu.

Previously, the rainy season would have been good for fishermen, including those who hunt for sardines. Now, due to erratic rain patterns, the supply of fresh water has decreased, leading to a sharp decline in sardines, Marivel said. Due to increasingly frequent cyclones between November and February, fishermen are also unable to go to sea for several days.

As fishermen face a decline in income, women are forced to venture into the deep sea to gather seaweed as an alternative source of income. But even that practice was affected by climate change.

Ten years ago, the women of Pamban Island began collecting seaweed as income from fishing began to decline. Marie, an algae collector on Pamban, says that this year she was only able to collect about 3 kg of algae per day, while 10 years ago she collected 20-25 kg per day.

Women are often asked to dive up to 3.5 meters (12 feet) under the sea without any protective equipment to collect algae.

Growing phytoplankton blooms in the sea due to irregular rains and rising sea temperatures cause erosion of seaweed and coral. As a result, small fish cannot breathe and die on the shore, says Gayatri Usman, station manager of Kadal Osai, a local radio station in the region.

The radio station, run by fishermen in Rameswaram, helps raise awareness about climate change through local traditions, folktales and songs. He recently offered 1,000 rupees ($11.6) for every fisherman who rescues a turtle.

“Our intention [is] make people aware of climate change. We cannot change climate change, but the idea is to raise awareness of it. Our motto is: think globally and act locally. Only by thinking about local solutions to climate change can we fight it globally,” Usman says.

But for many fishing families, it is already too late. The spate of arrests they and their comrades have faced in recent months means many want their future generations to stay away from fishing. “We would never want our children to be fishermen or to marry a fisherman,” says Marivel.