The number of venture capital firms in the US is falling as money flows to the biggest investors in technology

Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, picks her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

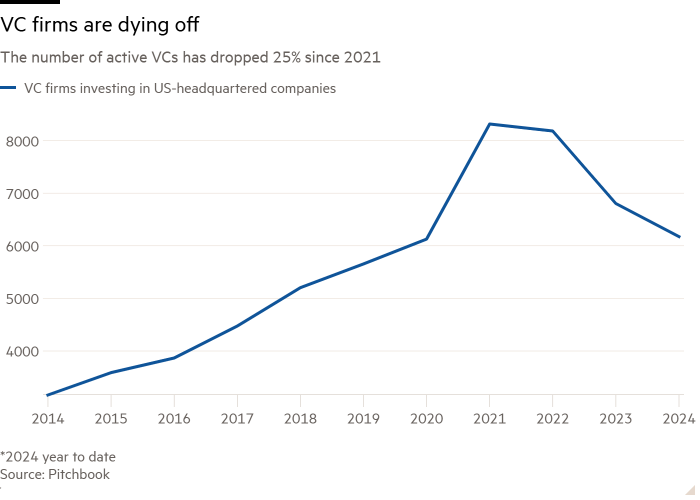

The number of active venture capitalists has fallen by more than a quarter from a peak in 2021, as risk-averse financial institutions focus their money on Silicon Valley’s biggest companies.

Sum of VCs investment in US-based companies fell to 6,175 in 2024 — down more than 2,000 from a peak of 8,315 in 2021, according to data provider PitchBook.

The trend has concentrated power among a small group of mega-firms and left smaller value capitals struggling for survival. It also distorted the dynamics of the US venture market, allowing start-ups like SpaceX, OpenAI, Databricks and Stripe to stay private much longer, while to thin out financing options for smaller companies.

According to PitchBook, more than half of the $71 billion raised by US equity capital in 2024 was invested by just nine companies. General Catalyst, Andreessen Horowitz, Iconiq Growth and Thrive Capital alone have raised more than $25 billion in 2024.

Many companies have thrown in the towel in 2024. Countdown Capital, an early-stage tech investor, announced it would shut down and return uninvested capital to its backers in January. Foundry Group, an 18-year-old VC with about $3.5 billion in assets under management, said the $500 million fund raised in 2022 would be its last.

“There is absolutely VC consolidation,” said John Chambers, former Cisco CEO and founder of start-up investment firm JC2 Ventures.

“Big boys [like] Andreessen HorowitzSequoia [Capital]Iconiq, Lightspeed [Venture Partners] and NEA will be fine and will continue,” he said. But he added that those venture capitalists who failed to secure big returns in the low interest rate environment before 2021 will struggle because “this is going to be a tougher market.”

One factor is a dramatic slowdown in initial public offerings and takeovers — the typical milestones at which investors cash out of startups. This stopped the flow of capital from VCs back to their “limited partners” — investors such as pension funds, foundations and other institutions.

“The time to return on capital has lengthened greatly across the industry over the past 25 years,” said LPs at a number of large US venture firms. “In the 1990s it probably took seven years to get your money back. It’s probably more than 10 years now.”

Some LPs have run out of patience. The $71 billion raised by US companies in 2024 is a seven-year low and less than two-fifths of the total in 2021.

Smaller, younger venture firms felt the pressure most acutely, as LPs chose to allocate funds to those with longer tenure with whom they already had relationships, rather than take risks on new managers or those who never returned capital to their backers.

“Nobody gets fired for putting money into Andreessen or Sequoia Capital,” said Kyle Stanford, lead VC analyst at PitchBook. “If you don’t sign up [to invest in their current fund] you could lose your place at the next one: that’s what gets you fired.”

Stanford estimated that the failure rate for mid-caps will accelerate in 2025 if the sector does not find a way to increase its returns on long-term capital.

“VC is and will remain a rarefied ecosystem where only a select cadre of firms consistently access the most promising opportunities,” 24-year-old venture firm Lux Capital wrote to its LPs in August. “The vast majority of new entrants are engaged in something that amounts to financial stupidity. We still expect as many as 30-50 percent of VC firms to die out.”