Private equity to lobby Trump for access to savers’ pension funds

Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

The private equity industry is preparing to lobby the incoming Trump administration to give it access to broad pools of capital it has historically been denied access to, including retirement savings, in a move that could unlock trillions for their companies.

The $13 trillion industry is hoping the new White House will revive the deregulatory effort of recent months Donald Trumpthe first presidency, which allowed private equity investments to be included in professionally managed funds.

The industry is now looking to push that first step, allowing tax-deferred defined contribution plans like 401k to support unlisted investments such as leveraged buyouts, subprime private loans and illiquid real estate deals, industry executives told the Financial Times.

Executives said the effort could give their higher-fee funds a chance to reach an investor class with at least the same assets as the sovereign wealth funds, pensions and foundations that traditionally back the world’s biggest groups such as Blackstone, Apollo Global and KKR.

Private capital and non-traded real estate funds have generally been limited to institutional investors or wealthy individuals because they often have higher leverage, less liquidity and less disclosure than traditional mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. They also generally have higher fees and have performance metrics that are more difficult to assess.

“We’re going to look for opportunities to give the average investor, if they want, the diversification of their portfolio and the same access to a private fund that wealthy individuals have,” said one Washington lobbyist. “There are 4,000 publicly traded [US] companies. Most people are invested in the market through these companies, but there are 25 million private companies.”

Industry executives told the Financial Times that the deregulatory push was akin to a “doubling of demand” for the private equity industry’s various funds.

Marc Rowan, CEO of Apollo, called the trillions in assets held by US 401k plans an opportunity for his industry. He expressed concern about the concentration in index funds owned by pension savers and questioned whether such investors should be limited to funds that offer daily liquidity.

“Sometimes I jokingly say, we subordinated the entire withdrawal of America to Nvidia’s performance. That just doesn’t seem smart. We will fix this and we are in the process of fixing it,” Rowan said at an Apollo event this fall. “In the US, we have between $12 and $13 trillion in 401k plans. What is invested in? They are invested in daily liquid index funds, mainly the S&P 500, over 50 years. Why? We don’t know.”

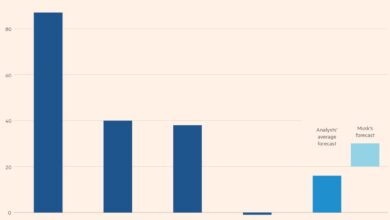

Wealthy individuals have flocked to private real estate and lending funds managed by Blackstone, Apollo, HPS and Owl Rock, among others, in search of higher returns and diversification into companies not available to public investors. A record $120 billion will flow into such funds in 2024, according to private equity data specialist Robert A Stanger & Co.

However, some private equity industry executives worry that retirement savers will not be able to distinguish between credible funds and those chasing lucrative fees. They recommend that private investments should be directed by fiduciaries rather than individuals directly selecting funds themselves.

The deregulatory window was opened by Eugene Scalia, son of the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, during the late stages of the first Trump administration. Then acting as head of the Labor Department, Scalia’s agency issued an Information Letter in June 2020 allowing private equity investments to be part of retirement-focused holdings, such as target-date funds and balanced funds.

“Adding private equity investments to such professionally managed mutual funds would increase the range of investment options available to 401(k)-type plan options,” the Department said at the time.

The idea was supported by Jay Clayton, then chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, who after leaving office joined the Apollo board.

Lobbyists and private equity groups are now exploring how they can advance Scalia’s massive private equity efforts. Scalia, who joined the law firm Gibson Dunn after Trump’s first term as president, successfully opposed efforts by the Biden administration to increase disclosures and regulations for private market funds.

“We will push for a regulatory regime that is pro-growth and that supports small businesses and provides more opportunities for everyday investors,” said Drew Maloney, head of the American Investment Council, the private equity industry’s main lobbying group in Washington.

PE executives believe the new administration will be less hostile to private dealmaking, which has been a central target of President Joe Biden’s antitrust authorities.

“We’re going to initiate business with the Trump administration,” Maloney said.