Chinese venture capitalists are forcing failed founders onto the debtors’ blacklist

Chinese venture capitalists are chasing failed founders, demanding personal assets and blacklisting them when they default, in moves that are throwing the country’s start-up funding ecosystem into crisis.

The hard-nosed tactics of venture capital providers are facilitated by clauses known as redemption rights, included in almost all financing agreements entered into during China‘s boom times.

“My investors verbally promised not to implement them, that they had never implemented them before – and in ’17 and ’18 it was true – nobody implemented them,” said Neuroo Education founder Wang Ronghui, who now owes investors millions dollars after her daycare chain faltered during the pandemic.

While in the USA they are relatively rare risky investmentShanghai-based law firm Lifeng Partners estimates that more than 80 percent of venture and private equity deals in China contain buyout provisions.

They typically require companies, and often their founders, to buy back investors’ shares plus interest if certain goals such as initial public offering deadlines, valuation targets or revenue metrics are not met.

“It causes a lot of damage to the entrepreneurial ecosystem because if a start-up fails, the founder essentially faces asset forfeiture and spending restrictions,” said a Hangzhou-based lawyer who represented several indebted entrepreneurs and asked not to be named. “I can never recover.”

Lifeng said in its recent report on repurchase rights that they have turned entrepreneurship into “a game of unlimited liability”. In 90 percent of investor lawsuits, the company said, founders were named as defendants alongside the companies, and 10 percent of the individuals ended up being added to China’s blacklist of debtors.

Once blacklisted, it is almost impossible for individuals to start a new business. They are also barred from a number of economic activities, such as traveling on planes or high-speed trains, staying in hotels or leaving China. The country lacks personal bankruptcy law, making it extremely difficult for most to escape debt.

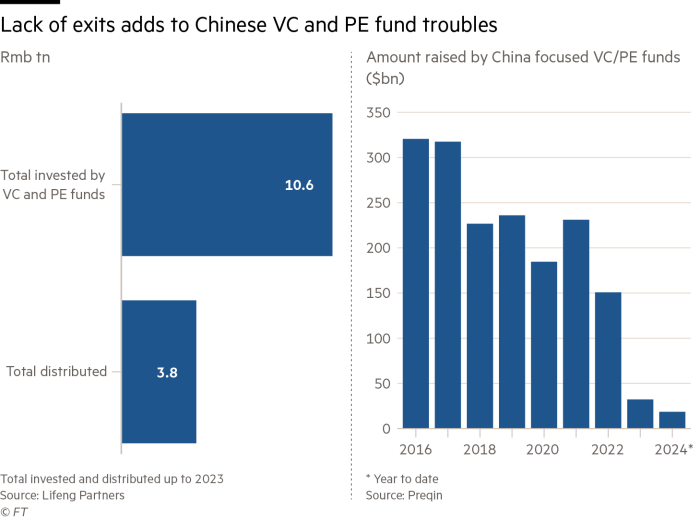

With Chinese funds and VC firms now struggling to return capital to their overseas investors, a growing number have turned to buyout clauses to recoup as much cash as possible. Lifeng estimates that 20 percent of all investor exits in 2021 and 2022 came from companies that bought back their investors’ shares, and that more than 10,000 VC or Chinese private equity-backed groups are facing buyout problems.

A start-up adviser who did not want to be named said the situation perversely encourages VCs to look for portfolio companies that are doing well but lack an immediate path to a sale or IPO.

“VCs are putting pressure on start-ups that can pay,” he said. “It’s not a venture – it’s a debt.”

The number of entrepreneurs who are affected by court cases continues to grow. Among them is Wang Ziru, who gained attention a decade ago as a brash young founder and raised tens of millions of renminbi for his tech media and review platform Zealer.

By 2021, with traffic declining, Wang left for an executive position at home appliance giant Gree. Then, on August 9 last year, a court in Shenzhen imposed spending restrictions on the 36-year-old for failing to pay a Zealer investor Rmb34 million ($4.7 million), an amount that grew with interest from the VC’s initial capital investment of $19 million Rmb, according to a lawyer familiar with the case. Wang lost his job a few days later.

The founder disputes the verdict and said on social media that he was not informed of the lawsuit and that the buyout provision was not triggered.

One of China’s best-known entrepreneurs, Luo Yonghao, turned his struggle to pay off the debts of his failed smartphone startup Smartisan into a spectacle, eventually selling enough iPhones and office chairs in live online video streams to pay off suppliers and clear his name from debtors. blacklist 2020

Then some of Smartisan’s investors came demanding that Luo pay hundreds of millions more in renminbi to buy back their shares.

“Investment is not a loan,” Luo wrote on social media platform Weibo in August last year. “When a venture capital business fails, one has to accept the outcome. Those who resort to vile tactics against entrepreneurs because they can’t handle the bottom line are undoubtedly unscrupulous capitalists.”

The cases have filled the Chinese courts. Records show Xu Mingqi lost his company and all of his other identifiable assets to investors after his Yeagood materials group failed to meet a promised three-year IPO deadline.

In 2021, China’s Supreme Court ruled that because his wife Zheng Shaoai also worked at Yeagood, one investor could seize joint assets including an apartment held in her name.

Wang, the 47-year-old founder of a childcare chain, even had her health insurance account seized by investors. She said her problems began in 2021, when funds linked to state investor Guangdong Cultural Investment Management demanded that their Rmb16 million shares be bought back with interest because her start-up failed to reach a Rmb500 million valuation.

Their lawsuit prevented a round of financing that was needed to offset the closure of 36 of the group’s day care centers related to the pandemic, she said. Now Wang owes about Rmb30m to funds linked to GCIM, Rmb11m to banks and potentially more to other investors whose buyout clauses have yet to be triggered.

GCIM did not respond to a request for comment.

“I have built my company into a leading industry – I have the ability and the desire – but every path I try to take is a dead end,” Wang said. “An unexpected turn of events left me permanently and completely captivated.”