China is stepping up its efforts to break the control of Boeing and Airbus in the aircraft market

China is ramping up its bid to break the stranglehold of Boeing and Airbus on the aircraft market, as the state-owned manufacturer of the country’s first domestic passenger jet seeks certificates to fly outside the country’s borders.

Comac’s heavily subsidized C919, which will make its first commercial flight in 2023, is already flown on domestic routes by China’s three major state carriers: Air China, China Eastern Airlines and China Southern Airlines. From this month, China Eastern will fly the C919 between Hong Kong and Shanghai, its first regular commercial route outside the Chinese mainland.

Yang Yang, the company’s deputy general manager of marketing and sales, told the Financial Times that the company aims to have the single-aisle plane flying in Southeast Asia by 2026 and to receive European certification as early as this year.

“We hope to operate more aircraft in China and thoroughly identify any issues before . . . bringing them to Southeast Asia,” he said.

The C919 is a key project in President Xi Jinping’s efforts China advance in the technology value chain, with the ultimate goal of challenging the Western duopoly of Boeing and Airbus.

Boeing’s financial difficulties and delivery delays, as well as broader industry supply chain problems that have left it and Airbus facing shortages of engines and components, have weighed on the global aviation sector and offered hope to newcomers.

The world will need 42,430 new aircraft over the next two decades, approximately 80 percent of which will be single-aisle aircraft, according to Airbus forecast 2024 Aviation consultancy IBA predicts Comac can increase its production of C919s — 16 of which were delivered to Chinese airlines by December — from one to 11 a month by 2040, by which time it can deliver nearly 2,000 aircraft.

However, Jonathan McDonald, IBA’s manager of classic and cargo aircraft, said that while Comac would eventually penetrate export markets, “for the foreseeable future, Airbus and Boeing will be the main suppliers of narrow-body aircraft to most airlines”.

Global certification and maintenance support remain significant obstacles to Comac’s ambitions for the C919 to operate overseas.

In an effort to strengthen its international presence, Comac opened new overseas offices in Singapore and Hong Kong in October.

The new offices were needed to help with new aircraft orders from customers, according to Mayur Patel, head of Asia for OAG Aviation.

But Richard Aboulafia, managing director of AeroDynamic Advisory, said building “elaborate facilities to support products in export markets is a very difficult and expensive business, and a necessary prerequisite to compete with Airbus and Boeing.”

While several carriers in Asia have expressed interest in the C919, some executives privately say they remain hesitant.

“Maintenance support is the main issue,” said a person close to Indonesia’s TransNus, which has already received three of Comac’s smaller ARJ21s and is considering flying the C919.

Comac’s path to obtaining foreign certification, especially from the European Union Aviation Safety Agency, is also challenging, according to analysts.

“The IBA does not expect the C919 to be certified in Europe in the near future,” McDonald said. “Europe has very strict certification parameters.”

Meanwhile, US FAA certification is likely to be complicated by US-China tensions.

EU and US regulators are often the “gold standard” for other global authorities, according to David Yu, an aviation industry expert at NYU Shanghai.

In parallel with the new C919, Comac is also developing its first wide-body aircraft, the C929. At one of China’s biggest air shows in Zhuhai in November, the company announced that state-owned Air China had become the first airline to pledge to fly the jet, which aims to compete with larger planes made by Airbus and Boeing, such as the 787 Dreamliner.

Sash Tusa, a UK-based aerospace and defense analyst, said that while the C929 offers China another chance to prove its technological advancement in the aviation sector, the country is still likely to rely on overseas engines for commercial aircraft. IBA estimates that the C929 will not enter service before 2040.

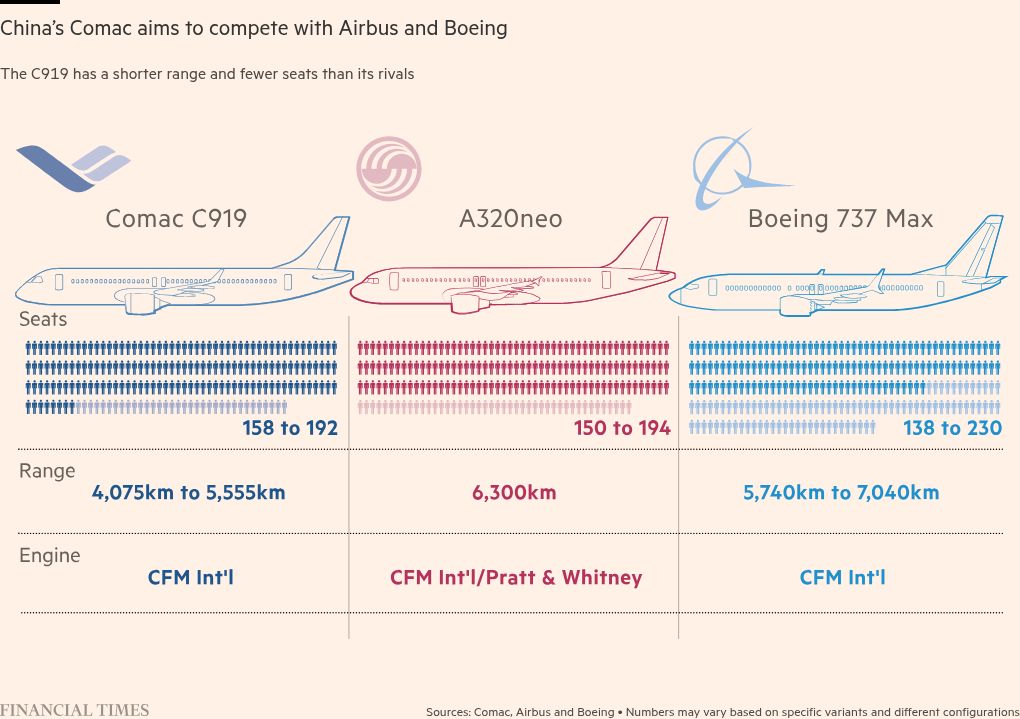

For the C919, key components are still Western-made. The jet engines are supplied by the French-American company CFM International, while the auxiliary power units are manufactured by the American Honeywell.

“Until now, [Comac is] building aircraft that are mostly Western in value but with Chinese structures,” said Aboulafia of AeroDynamic Advisory. “This makes production ramps dependent on the West’s willingness to continue supplying the systems, and, given the Trump presidency, there is no guarantee of that.”

Comac is unlikely to be able to gain any “fair share of the global market” in the next decade, Tusa said, but will provide an important “import substitute” for China’s domestic airlines.

“Airbus builds in China. Boeing does not,” he said. “So, Comac comes as a second supplier. Import substitution does not make you a competitor. That makes you an act of state policy.”

Additional reporting by William Langley in Guangzhou