The painstaking dismemberment of US Steel is a deal for the ages

Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

US Steel shares never reached the $55 Nippon Steel offered to buy the company in December 2023, in a cross-border tie-up that has angered politicians and steelmakers alike. This week they were trading around $32. So in a sense, outgoing President Joe Biden’s decision to crush the deal on the basis of national security is already old news.

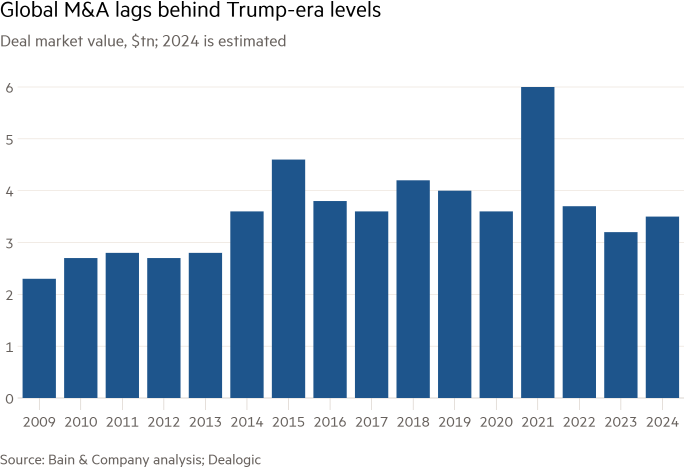

But there’s also something new: trying to understand the rules of the road for mergers and acquisitions. Many corporate advisers expected 2025 to be a relative fest, helped by Donald Trump’s more business-friendly presidency. The reality may be more complicated.

For now, there are indications that big is no longer bad, per se. The Biden administration has made no secret of its skepticism about companies that have been dominant in their field, such as Amazon. There was a lot of red tape: In recent years, US deals worth more than $10 billion have taken twice as long to close as they did a decade ago, according to Goldman Sachs.

Trump’s term could see a return to a simpler way of looking at antitrust policy, focused on traditional notions of consumer welfare—and paying less attention to things like competition for employees or the impact on other stakeholders. Bank of America chief Brian Moynihan and Goldman Sachs chief David Solomon predicted a more favorable market for mergers and acquisitions in 2025 thanks to the new occupant of the White House.

But if market power isn’t necessarily a deal breaker, foreignness still might be. Both Biden and Trump opposed Nippon’s takeover of US Steel. It’s not clear that this was rational: The Japanese company offered all kinds of concessions, including nearly $100 million in bonuses for American employees and keeping the company’s headquarters in Pittsburgh. Life is not fun for a steel worker.

If Trump is suspicious of takeovers with foreign buyers, such logic is unlikely to apply to domestic landscapes. It’s hard to put America first without nurturing — or maintaining — giant companies like Google parent Alphabet, chip maker Nvidia or megabank JPMorgan that can throw sand in the face of foreign rivals. This, in turn, is difficult to do without maintaining a hostile view of domestic corporate reproduction.

The key test will be the technology sector. Personnel changes at top regulatory bodies – for example, sharp-witted academic Lina Khan left as head of the Federal Trade Commission – suggest a softer but hard-to-give approach. New brooms may soon be tested: The so-called Magnificent Seven, which include Apple, Microsoft and Facebook owner Meta Platforms, have $530 billion in cash burning a hole in their balance sheets.

Meanwhile, US Steel could be a test case for what happens to losers. Domestic rival Cleveland-Cliffs previously expressed interest in a domestic M&A solution. Trump has suggested he can protect the company in other ways, using tariffs and taxation — interventions that make the merger calculus even more slippery. Making deals may become more common in 2025, but not necessarily easier.