‘Symbol of resistance’: Lumumba, Congolese hero killed before his prime | News from history

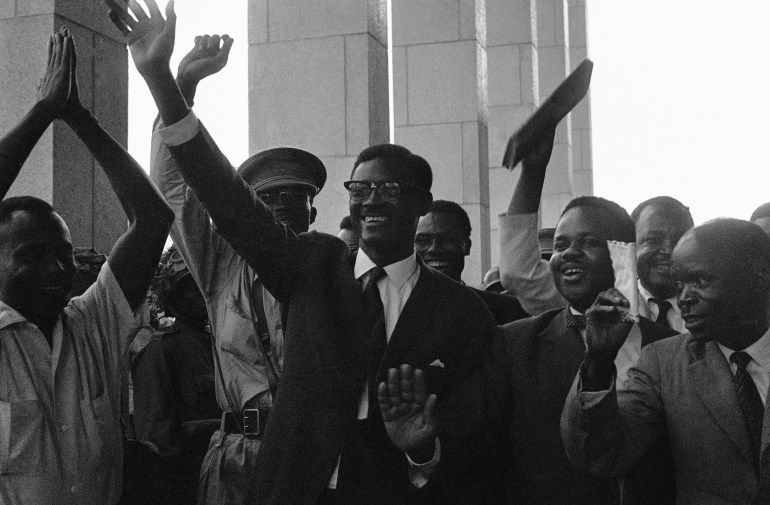

Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo – Shortly before noon on a Thursday in June 1960, 34-year-old Patrice Lumumba stood on the podium in the Palace of the Nation in Leopoldville (today’s Kinshasa) with a dream to unite his newly liberated country.

Standing in front of dignitaries and politicians, including King Baudouin of Belgium, from whom the then Republic of the Congo had just gained independence, the first prime minister in history delivered a stirring, somewhat unexpected speech that stirred Europeans.

“No Congolese worthy of the name will ever be able to forget that it was fighting against it [our independence] was won,” said Lumumba.

“Slavery was imposed on us by force,” he continued, as the king looked inside juice. “We remember the blows we had to endure morning, noon and night because we were ‘black’.

With independence, the country’s future is finally in the hands of its people, he declared. “We will show the world what the black man can do when he works in freedom and we will make the Congo the pride of Africa.”

But that promise remained unfulfilled, as only six months later the young leader was dead.

For years, the details of his murder were confused, but it is now known that Lumumba was killed on January 17, 1961 by armed Congolese, aided by the Belgians and with the tacit approval of the United States.

Sixty-four years later, Lumumba remains a symbol of African resistance, while many Congolese still carry the burden of his abortive legacy – whether they support his ideas or not.

‘I was shaken by his death’

“When I learned of Lumumba’s death, I was shocked,” said 85-year-old Kasereka Lukombola, who lives in the Virunga neighborhood of Goma, in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

Its gold-painted Western-style house, unusual in this region, was built in the colonial era and is a reminder of the remnants of almost 80 years of Belgian rule.

Lukombola was born during World War II, he said. “At that time, a black man in Africa could not stand up to the white settlers for certain reasons, including the color of his skin and the fact that he was enslaved. Those who dared to challenge the whites were either imprisoned, beaten or killed.”

He was 20 years old when Lumumba was killed. Although it took weeks before news of his death broke, Lukombola remembers that night as one of the “darkest” he has ever known.

“I remember being in my village in Bingi [when I heard the news]. I regretted it, his death shook me. I didn’t eat on that date, I had insomnia,” he said and added that he still remembers it today as if it were yesterday.

Lukombola accuses the Wazunga (a term meaning “foreigners” but generally used of Belgian colonists) of being behind the assassination.

“The Belgians were racially dividing the Congo, and Lumumba resented it. He encouraged us to fight tooth and nail to get rid of the colonizers,” he said.

“He discovered certain conspiracies of the colonists against us, the Congolese people. They wanted to enslave us forever. Then the Belgians developed a hatred for him, which led to his murder.”

Lukombola believes that if Lumumba had not been killed, he would have turned the country into a veritable “El Dorado” for millions of Congolese, based on the vision he had for his people and the continent as a whole.

Tumsifu Akram, a Congolese researcher based in Goma, believes that Lumumba was killed at the behest of certain Western powers who wanted to keep the Congo’s natural resources.

“The decision to eliminate the first Congolese prime minister was made by American and other officials at the highest level,” he told Al Jazeera.

Although Lumumba had friends both inside and outside the country, “as many as they were, his friends were not as determined to save him as his enemies were determined and organized to finish him off,” Akram said. “His friends supported him more with words than deeds.”

Only the tooth remained

Just days after Lumumba delivered his Independence Day speech on June 30, 1960, the country began to descend into chaos. There was an armed rebellion and then the secession of the mineral-rich Katanga province in July. Belgium sent troops to Katanga. Congo then asked for help from the United Nations, which, although it sent peacekeepers, did not deploy them to Katanga. So Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union for help – a move that upset Belgium and the US.

In September, President Joseph Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba from the government, which he ignored. Soon after, a military coup led by Congolese Colonel Joseph Mobutu (later known as dictator Mobutu Sese Seko) removed him from power completely. Lumumba was placed under house arrest from which he escaped, only to be captured by Mobutu’s forces in December.

On January 17, 1961, Lumumba and two associates, Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, were then flown to Katanga – beaten and tortured by soldiers during the flight and at their destination.

Later that day, all three were executed by a Katangan firing squad under Belgian supervision.

At first, their bodies were thrown into shallow graves, but later they were dug up, chopped into pieces, and the remains dissolved in acid.

In the end, just one tooth Lumumba’s remains, which were stolen by a Belgian policeman and returned to Lumumba’s relatives only in 2022.

In the years after the murder, Belgium admitted that it was “morally responsible for the circumstances that led to the death”. In the meantime, the information that they exposed also came to the public Involvement of the American CIA in a plot to kill Lumumba.

‘Big mistake’?

At his home in Goma, Lukombola recounted all the “firsts” he had experienced during his country’s complicated history, including participating in the first municipal elections in 1957 – in which he voted for Lumumba’s Congolese National Movement (MNC) party “because I was convinced that he has a great vision for our country. It was out of a sense of pride,” he said.

He told how he was around during the riots on January 4, 1959; the declaration of independence of the Congo on June 30, 1960; the secession of Katanga and South Kasai between July and August 1960; and the joys of Zaire’s economic and political heyday in the mid-1960s.

Having lived through the reigns of all five Congolese presidents, Lukombola understands the “enigma” that is the DRC and has seen how much it can change.

His only regret, he said, is that many historical events took place after Lumumba’s death. “If he were alive, he would restore our glory and greatness.”

But not everyone views Lumumba’s legacy with such awe and kindness.

Grace Bahati, a 45-year-old father of five, believes that Lumumba is the cause of some of the misfortunes that have befallen the DRC and that the country is still struggling with.

According to him, the first prime minister wanted Congo’s immediate independence too quickly, and the country lacked enough intelligence to lead it after the departure of the Belgians.

“Lumumba was in a hurry to claim independence. I found that many of our leaders were not ready to lead this country, and that is a shame,” Bahati told Al Jazeera. “In my opinion, that was a big mistake on Lumumba’s part.”

Dany Kayeye, a historian from Goma, does not share this opinion. He believes that Lumumba saw from afar that independence was the only solution, given that the Belgians had exploited the country for almost 80 years and the Congolese were the ones suffering.

“Lumumba was not the first to demand the immediate independence of the country. The first to do it were the soldiers who came from the Second World War, fighting alongside the colonists,” Kayeye also pointed out.

But only after Lumumba’s alleged “radicalization” – when it was seen that he was building ties with the Soviet Union – did he find himself in the crosshairs of the West because they considered him a threat to their interests during the key period of the Cold War, the historian said. Congolese like Mobutu Sese-Sek were then used in maneuvers against him.

“For a long time, Congo was envied for its natural riches. The Belgians did not want to leave the country, and the only way to continue exploiting it was to anarchize it and kill its nationalists,” explained Kayeye. “It was in this context that Lumumba, his friends Maurice Mpolo, then President of the Senate, and Joseph Okito, then Minister of Youth, died together.”

‘Fought for justice’

Jean Jacques Lumumba is the nephew of Patrice Lumumba and an activist who advocates the fight against corruption in the country.

The 38-year-old grew up in Kinshasa, raised by Lumumba’s mother and younger brother, but was forced into exile in 2016 because he denounced corruption in the environment of former Congolese President Joseph Kabila.

For him, his uncle remains a symbol of an honest and better Congo, someone from whom he takes inspiration in his own activism.

“My family tells me that he was an atypical personality. He was quite honest and direct. He had a sense of honor and a search for the truth from early childhood until his political struggle,” Jean Jacques told Al Jazeera.

“He fought for justice and fairness. He himself rejected corruption”, he added, calling corruption “one of the evils that characterize developing countries”.

“[Patrice Lumumba] wanted prosperity and development… This is an inspiration in the struggle I continue to lead, for the emergence of the African continent.”

Jean Jacques believes that Lumumba no longer belongs only to the DRC and Africa, but also to all those who want freedom and dignity around the world.

Although he never met his uncle, he is pleased that his memory and legacy live on.

And although it came to a tragic and devastating end, for Jean Jacques Lumumba’s death is also something that perpetuates his name and the battles he fought.

African leaders should honor the memory of people like him and others who paid with their lives to build “a developed, radiant and prosperous Africa, ready to assert itself in the concert of nations,” the younger Lumumba said.

Lumumba’s ‘eternal’ legacy

More than six decades after Lumumba was assassinated, the DRC is in the midst of multiple crises – from armed insurgencies to resource extraction and poverty.

Although it is a country of immense natural wealth, it has not found its way to the majority of Congolese – something many in the country attribute to continued exploitation by internal and external forces.

Daniel Makasi, a resident of Goma, believes that the colonialism that Lumumba was so determined to fight is still strong – although it manifests itself in different ways today.

“Today there are several forms of colonization that continue through multinational companies that exploit resources in DR Congo and that do not benefit ordinary citizens,” he told Al Jazeera.

He added that Africans should channel the spirit of Lumumba to stop such neo-colonialism as much as possible, so that they can enjoy the fullness of their natural wealth.

Lumumba managed to transform the country in a short time, making Congolese “more proud”, and that makes him “eternal”, Makasi said, urging people to follow his example.

Others also agree that future generations owe Lumumba an “immeasurable” debt for what he started.

“For me, Patrice Emery Lumumba is a symbol of resistance to the imperialist powers,” said Moise Komayombi, another Goma resident, recalling a June 1960 Independence Day speech that Belgians considered “brutal attack” but it inspires many Africans to this day.

“He inspired us to remain nationalists and protect our homeland from all forms of colonization,” Komayombi said, reminding himself that Lumumba’s work is still not finished.