The coming battle between social media and the state

“Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” is the important question posed by the Roman poet Juvenal, translated by the English author Alan Moore as “Who watches the watchmen?”.

But it is perhaps a question with a complacent implicit assumption. It presupposes that it is possible to watch the watchmen — and all that one needs to do is work out how this is done and by whom.

Regulation, however, is not magic. Just because one wants a thing to be regulated, that does not make it capable of actually being regulated. If a thing is unpleasant or unwelcome, the instant demand is that something should be done, and that the unwanted thing can be regulated so it cannot happen.

The notion that all we need to make the world a better place is “better regulation” is deeply embedded in our culture. And one thing for which the cry for regulation is made is social media platforms. If only they were “better regulated”, the popular sentiment goes, then various political and social problems would all be solved.

But there are two problems with regulating social media platforms. The first comes from the very technology that gave rise to this fairly recent but now almost ubiquitous phenomenon. The second is that to impose effective regulation against unwilling platforms will require determined, unflinching governmental action and political will — the possibility of which the platforms are now doing what they can to avoid.

At base social media is about the ability of anyone with an internet connection to use an online platform to say anything they want about anybody to anyone. As soon as what they want to say is typed — or recorded in video and audio — all they need to do is press enter and it is published — or broadcast — to the world.

This ease of publication or broadcast contrasts with the position up to about 30 or 40 years ago where a private individual would normally have to pass a number of gatekeepers — at newspapers, publishing houses and broadcast stations — before having what they wanted to say go far beyond their immediate circle.

The law in turn followed this restrictive model. Liability for, say, defamation or infringement of copyright, or for non-compliance with broadcasting standards, would usually bite at the moment the gatekeepers permitted publication or broadcast. For that step was a solemn moment and those permitting wider circulation had onerous responsibilities.

Yes, of course, it was open to eccentric and determined individuals to “vanity press” a book, or to promote home-printed pamphlets, or even start a pirate radio station. But these were intensive and expensive courses of action that would not cross the minds of normal people.

And then came along the world wide web, user-friendly internet browsers, and the social platforms that made online publication easy. Everyone could publish to the world about anything they wanted.

How was this constant babble to be regulated? Would it be possible? Or would it be as futile as seeking to regulate everyday conversations in the home or in the street?

One idea was to try to make the platforms themselves like the gatekeepers of old: to treat the social media companies as “publishers” of what was published by their users. But the obvious problem was that the platforms did not have, and could not have, any form of prior approval to what was published. All they could do would be after the event, once the unwanted thing was already published. They were gatekeepers only able to close the gate after the animals had bolted. They could un-publish but not publish.

Platforms thereby lobbied successfully for legal liability only to be incurred if a valid takedown request was not granted. And in any case this approach only worked where there were pre-existing individual legal causes of action: it made sense in respect of defamation of a specific identifiable individual.

But mass disinformation and misinformation often break no private law rights of individuals. The real victim instead is healthy public discourse. Another challenge was dangerous information in respect of self-harm and suicide. And also the promotion of criminal activity, such as child abuse or terrorism.

These problems were stark, and they required more than mere takedown notices by complainants. Indeed, there would often be no complainants aware of such material, only those seeking to consume it. Constant vigilance would be required.

One way of addressing this would be for the social media platforms to employ complex and expensive systems. This would be an immense cost imposition for platforms that primarily just wanted to monetise data and to sell advertising on the back of the social media postings of users. But it would be an imposition that platforms would only accept if there was no alternative.

Those following the relationship between Big Tech and public policy can get distracted — and exhausted — by the constant rush of events on 24-hour media and the loud personalities. As Madness sang in “Our House”: there’s always something happening, and it’s usually quite loud.

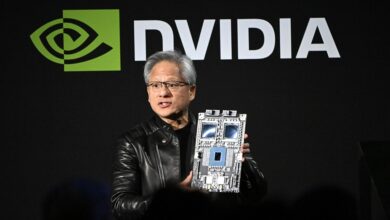

It is more difficult to take a step back and to analyse situations both in terms of tactics and strategy of the companies and the authorities involved. Impulsive figures such as Elon Musk, the owner of X (previously Twitter), and inconsistent decision makers such as Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg, can misdirect us from what their companies are rationally seeking to achieve.

And there have been a couple of events that indicate that such companies are not as strong and powerful as their cheerleaders and critics seem to believe. Indeed, the providers of American social media platforms are weak in the face of a particular obstacle. For it is weakness, and not strength, that explains their recent behaviour.

The obstacle is regulation by jurisdictions outside the US — primarily in the European Union, but also elsewhere such as Brazil and China. The social media platforms have realised that they cannot win the battles with foreign governments and legal systems by themselves. They are not powerful enough to solve their own problems. They need help.

One example here is how X and other business interests directed by Musk went through the motions of opposing the order of the Brazilian Supreme Court to take down offending material, only to capitulate and to perform the obligations imposed by the Brazilian judicial system and local law. X huffed and puffed, but the only house that was blown down was its own.

This corporate weakness in the face of determined state action should not be surprising. In any ultimate battle, the state will prevail over a corporation for the simple reason that a corporation as a legal person only has legal existence and entitlements to the extent set out by legislation. Those who control the law can, if they want, control and tame any corporate in their jurisdiction.

This is why, for example, the most powerful corporation the world had then seen — the East India Company — was summarily dissolved by the British parliament in 1874. It is also why the Bell System of telecommunications companies was broken up by US antitrust law and policy in the 1980s. Companies can be very powerful — but there is always something stronger on which they depend for legal recognition.

Large companies therefore place great reliance on being able to influence public policy and lawmaking. This explains what Meta did, for instance, with the appointment of the pro-European former UK deputy prime minister Nick Clegg as vice-president of global affairs and communication. That was a good choice for a company seeking to constructively influence the formulation and implementation of EU policy.

But there is only so much that can be done by utilising contacts and quiet consultation. The friendly approach did not prevent the EU’s Digital Services Act. It did not prevent a €797.72mn fine for antitrust breaches. It did not prevent a €1.2bn fine for data breaches. Meta’s policy of constructive dialogue with the EU was failing badly.

There was a looming contradiction between what Meta wants from its social media platforms in the jurisdiction of the EU and what the EU is willing to accept. Smiles and handshakes were no longer enough.

The re-election of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States provided Meta with a glorious opportunity to pivot from futile co-operation with the EU to confrontation and coercion. If Meta could get the US government onside in its battles with the EU and other jurisdictions, then it would maximise its chances of success.

In his Facebook announcement this week of changes to various policies, Zuckerberg candidly said that he wanted to “work with President Trump to push back on governments around the world. They’re going after American companies and pushing to censor more. The US has the strongest constitutional protections for free expression in the world . . . The only way that we can push back on this global trend is with the support of the US government.”

This was listed in his pre-prepared statement as the sixth policy change, but it was plainly the most important — for it also explained the other five points, which included abandoning fact-checking and moving content moderation from California to a “less biased” Texas. Everything in that statement went towards aligning Meta with the values and priorities of the new administration.

For a corporation in the predicament of Meta this makes perfect commercial sense, even if it does violence to previously expressed sentiments. This is not an example of a company suddenly acting irrationally, but of a company rationally responding to one political development so as to facilitate defeating a regulatory challenge.

And it is not the only tactic serving this broader commercial strategy. The leaders of many tech companies have every interest in promoting the new US government and in weakening resolve in the EU. Member states with leaders sympathetic to Trump, such as Hungary and Italy, are being courted alike so that EU policy can be weakened from the inside.

The tech giants are adopting this robust strategy not because they are strong — they know that, like X in Brazil, they cannot take on any determined government or legal system in a significant market and win. They are doing this because they know they are weak, and that they need allies. Their business model depends upon it.

And as the business models of most social media platforms require engagement above all — for without engagement you cannot have data mining and monetising and advertising — it really does not matter that the engagement is generated and amplified by misinformation and disinformation.

Moderation and fact-checking are expensive. If the social media platforms were obliged, under pain of legal sanction, to make such moderation and fact-checking work, then that would be the commercial way forward. International corporations will tend to comply with the applicable law, and the expense of compliance is a cost of business.

But not having such procedures and policies in place is far cheaper and more profitable. So if they can avoid such obligations they shall — and if “soft” lobbying does not work then they will look to governments to do the hard work of coercion.

If Meta and X were confident in heading off the regulatory impositions of the EU, Brazil and elsewhere, they would not need to swing behind Trump and the new administration. The fact that they are doing so openly and unapologetically — indeed shamelessly — means they know they have a challenge, and one which they may not meet. They know that certain foreign governments and legal systems are capable of winning any head-to-head regulatory battle.

For as the surrender of Musk and X to the Brazilian courts shows, state power is likely to always ultimately win against the platforms if tested. But that was an extreme situation: regulation is an ongoing phenomenon, and exciting and dramatic court cases should be an exception. More useful on a day-to-day basis is for regulators to be put in their place.

The recent appointments at board level at Meta look like it is preparing for battle, and one in which its current commercial model requires it to defeat the aims of foreign governments. The new appointments make a lot of strategic sense.

And if it does play this situation well, with the US government bullying other states for the benefit of the platforms, this is a battle and a war that the tech companies can win — not because of how they played to their strengths but because of how they covered their weaknesses.

The question is now whether the EU, Brazil and others have the determination and the stomach for what will become an ugly public multinational row.

Nonetheless there is a fight ahead: over who shall regulate the social media platforms that in turn are influential in shaping (and contaminating) public discourse.

David Allen Green, a regulatory and media lawyer, is an FT contributing editor